Drone Flight Planning

Flying your drone UAV in a different location requires some preparation, much like the flight plan for a regular aircraft. If you have not properly prepared for a flight outside of a drone practice field or your back yard, you are not “ready to fly”. You’ve heard the phrase: if you fail to plan then you plan to fail.

Flight Planning Check List:

1: Check the weather at the flight location. One source is the Weather Channel app, but if you have learned how to read TAFs and METARS in your UAV operator training, this would be a good time to use those skills using an app like AeroPlus Weather or Aviation WX. If the winds are more than what you feel safe with, then wait until a better time.

Drone Flight Planning

Flying your drone UAV in a different location requires some preparation, much like the flight plan for a regular aircraft. If you have not properly prepared for a flight outside of a drone practice field or your back yard, you are not “ready to fly”. You’ve heard the phrase: if you fail to plan then you plan to fail.

Flight Planning Check List:

1: Check the weather at the flight location. One source is the Weather Channel app, but if you have learned how to read TAFs and METARS in your UAV operator training, this would be a good time to use those skills using an app like AeroPlus Weather or Aviation WX. If the winds are more than what you feel safe with, then wait until a better time.

|

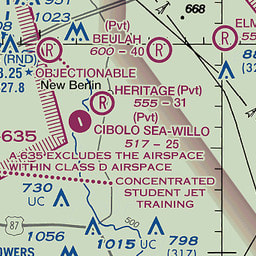

2: Check the location of your flight with AIRMAP.IO or chart the location on a printed aeronautical chart. Be sure the location does not fall within a restricted or “do not fly” zone.

Be careful not to overlook private airports which are marked with the circle-R. Heliports are marked with a circle-H, and Ultralight fields are shown with a circle-F. You are most likely to encounter low altitude aircraft near these last three. Become familiar with the chart symbols. Other restrictions may be found near schools, hospitals, even some private properties (Check NoFlyZone.org). If the flight location is in a no-fly area or too close to an airport, you will need to declare a no-go for that location.

|

3: Next check for NOTAMs and TFRs flight restrictions at the FAA’s web site: http://tfr.faa.gov/tfr2/list.html. Special restrictions and temporary no-fly zones may be created for major sports events, air shows or political events. If restrictions will be in effect for your expected flight time, put off the flight to a better time. These restrictions apply even for “hobby” flights

|

4: Any commercial operations under an exemption ABOVE 200 ft will require filing a Civil COA Request in advance (15 days is recommended), which must be filed online HERE. A sample form can be found HERE (This form is for informational purposes only). Check the specific conditions of your Exemption. Operations under 200 ft are permitted by a blanket COA for exemption holders. (As of March 23, 2015)

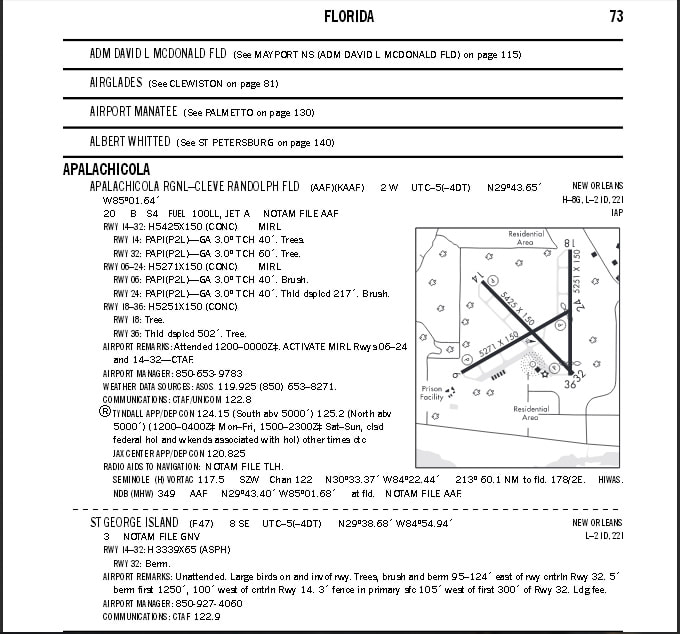

If the operation is to be near an airport (within 5 miles), print out the phone number and operating frequencies of the appropriate airport from the FAA’s online directory and make contact in advance of the flight date and time. For example, this is the information for David McDonald Field at Apalachicola. In some situations it might be advisable to monitor the appropriate local UNICOM radio channel. Know where the runways are so that you can anticipate landing patterns for specific wind conditions. Never fly beneath a landing pattern. |

5: Once you have reached the launch location check for obstructions, hazards and obstacles, like power lines, and trees or buildings that could obstruct your ability to maintain visual line of sight. Keep a safe distance from active highways to prevent accidentally flying too close to traffic: if a driver is distracted by your low flying aircraft you could be responsible for an accident. If conditions are not safe, select an alternate location.

|

6: Check the wind conditions. You will need to take the wind direction into consideration in case your aircraft might drift where you don’t want it (eg. trees). Check the treetops for the tell-tale signs of higher winds at tree top level. Use an portable anemometer to check and log the wind speed and direction. Be aware that changes in wind conditions can also appear between buildings (eg: condos) or over water. Again, if the wind speed is more than what you consider safe to fly, declare a no-go. Also beware of weather fronts (distinct differences in sky conditions) that could be hiding wind gusts or wind shear conditions, which are often the real cause behind mystery “fly away” drones. If your drone’s max speed is 30 mph and the upper level wind is 35 mph, the wind wins. Don’t be afraid to cancel the mission if the forces of nature are against you. Better to fly safely another day.

|

7: Set the boundaries of your launch operation area. Determine where you want to go and how you plan to go there. As you plan to start your flight be sure to clear the launch operation area of anyone not involved in the flight. At this point you should initiate a “sterile cockpit” as you begin to prepare for the job at hand as the PIC/operator. Your observer would now be responsible for preventing distractions from onlookers until after the drone has landed and shut down.

If none of the previous steps have resulted in a no-go condition you can then proceed with your compass calibration and the rest of your normal flight start up checklist.

Failing to follow safe procedures for a UAV “mission” is an invitation to trouble. Every time I have had a problem with a flight, in hindsight I can point to a where I missed or overlooked a danger signal, whether it was a decision to launch from too close to a commercial pool pump (magnetism threw off the GPS), failed to notice a control battery warning symbol (lost control signal), or failed to hold at a medium altitude before going higher (unexpected wind gusts).

A “no-go” decision condition can appear at any point in the process. Failure to recognize a no-go condition can lead to unpleasant results. Accidents (fly-aways, Controlled Flight Into Trees, water landings, etc.) stemming from poor decision making usually fall under one of these headings:

1: Anti-authority: “rules don’t apply to me”

2: Impulsive: “get it done”

3: Invulnerability: “won’t happen to me”

4: Macho: “I can do anything”

5: Resignation “I can’t do it”.

That is what the FAA describes under the heading of Aeronautical Decision Making , and UAV operators are no less subject to the pitfalls. Because of the high reliability of the aircraft we use, most failures and accidents can be attributed to poor judgement and bad decisions by the operator. And that includes deciding not to plan ahead. The alternative is… inspect for damage, replace broken props, don’t be stupid next time.

If none of the previous steps have resulted in a no-go condition you can then proceed with your compass calibration and the rest of your normal flight start up checklist.

Failing to follow safe procedures for a UAV “mission” is an invitation to trouble. Every time I have had a problem with a flight, in hindsight I can point to a where I missed or overlooked a danger signal, whether it was a decision to launch from too close to a commercial pool pump (magnetism threw off the GPS), failed to notice a control battery warning symbol (lost control signal), or failed to hold at a medium altitude before going higher (unexpected wind gusts).

A “no-go” decision condition can appear at any point in the process. Failure to recognize a no-go condition can lead to unpleasant results. Accidents (fly-aways, Controlled Flight Into Trees, water landings, etc.) stemming from poor decision making usually fall under one of these headings:

1: Anti-authority: “rules don’t apply to me”

2: Impulsive: “get it done”

3: Invulnerability: “won’t happen to me”

4: Macho: “I can do anything”

5: Resignation “I can’t do it”.

That is what the FAA describes under the heading of Aeronautical Decision Making , and UAV operators are no less subject to the pitfalls. Because of the high reliability of the aircraft we use, most failures and accidents can be attributed to poor judgement and bad decisions by the operator. And that includes deciding not to plan ahead. The alternative is… inspect for damage, replace broken props, don’t be stupid next time.